With a bit more evidence, it’s clear that last year’s “urban exodus” was always a bit more complex than this neatly labeled theme implied. By now, we all understand that lots of people left the largest, most expensive cities for cheaper, less dense markets. But an “urban exodus”? Did everyone leave Manhattan for a spacious suburban home in Fairfield County? That’s ridiculous.

An early mentor often said that reality is never as good or as bad as it seems. Things are messy. We try to simplify complex issues to make sense of them. Since we don’t always have the time to do the work, we welcome tidy catch-phrase explanations that provide conclusions in a neat little package.

The “urban exodus” described a narrow subset lazily applied to the whole. That’s a common problem with labels.

Another challenge is when we use a static label in a dynamic environment. Shifts in supply and demand will affect price, which causes a feedback loop back to supply and demand.

It’s a fact that many renters chose to move out of expensive cities to homes in the suburbs. Not all renters wanted to or could move. But many did. And since the market cannot shift supply as quickly as demand, housing prices fell in the cities and rose in the suburbs.

So now what?

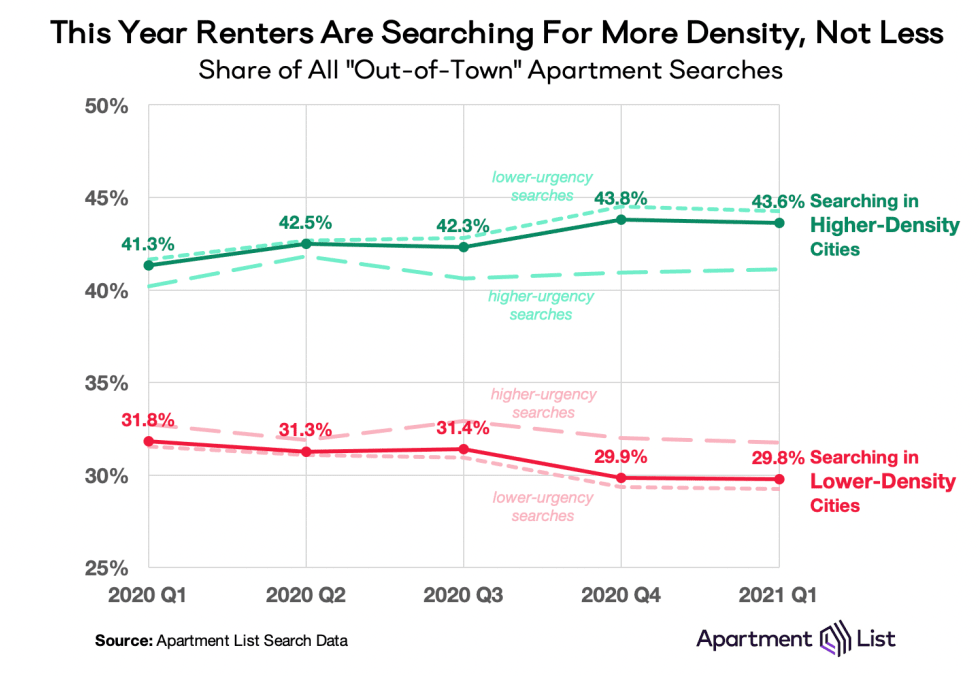

With vaccinations rising and COVID fears receding, rent prices in cities are recovering. I was interested to see the Apartment List Rental Migration report that shows a recovery in search activity across higher-density cities.

There’s no doubt that COVID has accelerated some significant trends in remote work and a growing preference for living in smaller, more affordable cities. These trends had already been in place before COVID, driven by new technology and more evolved employer views on WFH/WFA.

The point is that large cities are not dead, nor were they ever likely to be. It’s not black or white. As I learned long ago, it’s never as good or as bad as it seems.